On Simpletons

In which I revisit a classic...

I’ve been rereading (or listening to) classic SFF novels I read as a child and teen, but particularly ones I suspect went at least partially over my head at the time. I’ve gone through Solaris by Lem, Dune by Herbert, The Left Hand of Darkness and The Dispossessed by Le Guin, His Dark Materials by Pullman, etc. Now I’m on to A Canticle for Leibowitz by Miller. A post-apocalyptic, widely-nuked world in which knowledge is feared for how it was used in the past and people of learning are reviled. The passage below describes the great “Simplification” that took place after the war. Just takes a slight cross of the eyes to see the relevance today. What if the nukes were financial? What if the “princes” of the past were the leaders of the Simplification? Published in 1959, but still giving:

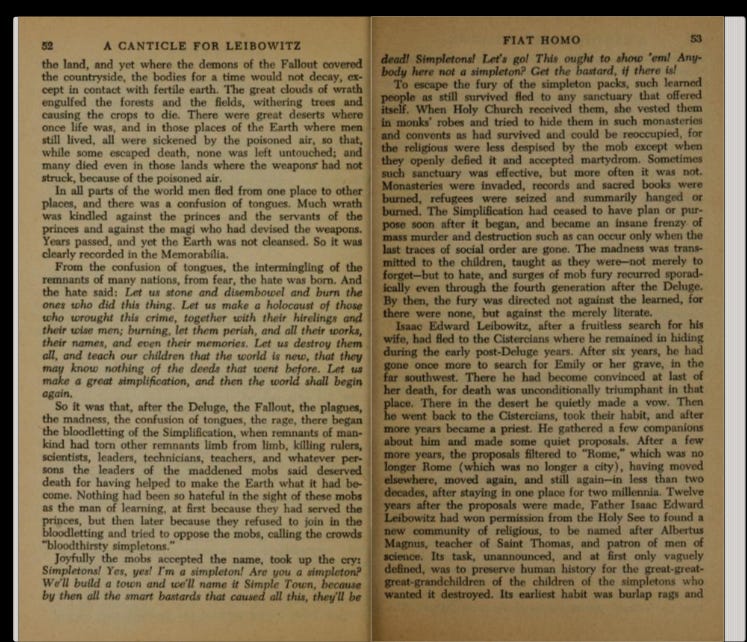

So it was that, after the Deluge, the Fallout, the plagues, the madness, the confusion of tongues, the rage, there began the bloodletting of the Simplification, when remnants of mankind had torn other remnants limb from limb, killing rulers, scientists, leaders, teachers, and whatever persons the leaders of the maddened mobs said deserved death for having helped to make the Earth what it had become. Nothing had been so hateful in the sight of these mobs as the man of learning, at first because they had served the princes, but then later because they refused to join in the bloodletting and tried to oppose the mobs, calling the crowds “bloodthirsty simpletons.”

Joyfully the mobs accepted the name, took up the cry: Simpletons! Yes, yes! I’m a simpleton! Are you a simpleton? We’ll build a town and we’ll name it Simple Town, because by then all the smart bastards that caused all this, they’ll be dead! Simpletons! Let’s go! This ought to show ‘em! Anybody here not a simpleton? Get the bastard, if there is!

Woof. We are approaching the Simplification, people.

In other notes: I forgot how funny it could be. I swear that those guys who wrote their SF on those dime-an-hour typewriters at the library were incentivized to write clear, quick prose that centred on an fulcrum between the external reality and the inner monologue. I sometimes wonder if the shift between these modes in the text had to do with the time running out and no more plot to expand on for the day. Works well, in the end.